Lazar Thurakkal Sebastine

Lazar Thurakkal Sebastine is an established classical musician hailing from Cochin in Kerala, India. Growing up in a musical family, Lazar himself spent 7 years studying music full-time in India, first on a 4-year diploma course at Radha Lakshmi Vilasam (RLV) College of Music and Institute of Fine Arts, the second largest arts institute in India, and after his graduation, in 1988 at the Sree Swathi Thirunal College of Music (SST) through a 3-year course. Lazar moved to Singapore in 2000 for a teaching position, and has since then taught many students and performed all over the world, from Russia to Macau. In this interview, he shares with us reasons why he doesn’t mind teaching infants how to play the violin, and also offers us a glimpse into an excitingly different world of music, which though distinct from the Western tradition, is in its own way classical.

How did this all start? What got you into music proper?

My entire father’s side of the family was very musical, though none of them had learnt it formally. My father himself performed as a violinist in addition to his day job as a plumber. Although it was a part-time occupation, he performed so much it took up a lot of his time. In many ways he also fit the stereotype that existed at that time that all musicians were heavy drinkers. As he was unfortunately dying from the effects of his drinking habit, he forbade anyone of his children from going into music as he did not want anyone of us dying an early death like him.

After that my brother took care of me. After my matriculation, however, my brother saw that I was talented and decided to send me to the RLV College of Music for a 4-year diploma course. So that’s how I first got into music proper.

So what instrument did you first learn?

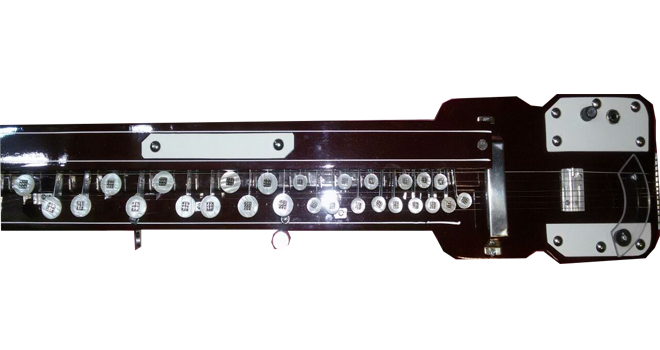

The Bul-Bul Tarang

I first picked up the Bulbul Tarang, which is a typewriter-like instrument.

The Harmonium

After that I picked up the Harmonium which is kind of like a keyboard, accordion hybrid.

My main instrument during my college years was the violin.

In addition to this, rhythm was always something that felt internal to me. As a child, I would always hit different surfaces and frequently ended up with blisters on my wrists. During my time in college, I would go to the percussion department during breaks and have a chat with the people there. At the same time I’d be able to learn somethings from them.

I understand that Indian music has been around for longer than its Western counterpart, and the whole concept of writing notes on bars is a very Western concept. I’m therefore really curious - how Indian classical music is transmitted and taught, if it’s not through Western-style scores?

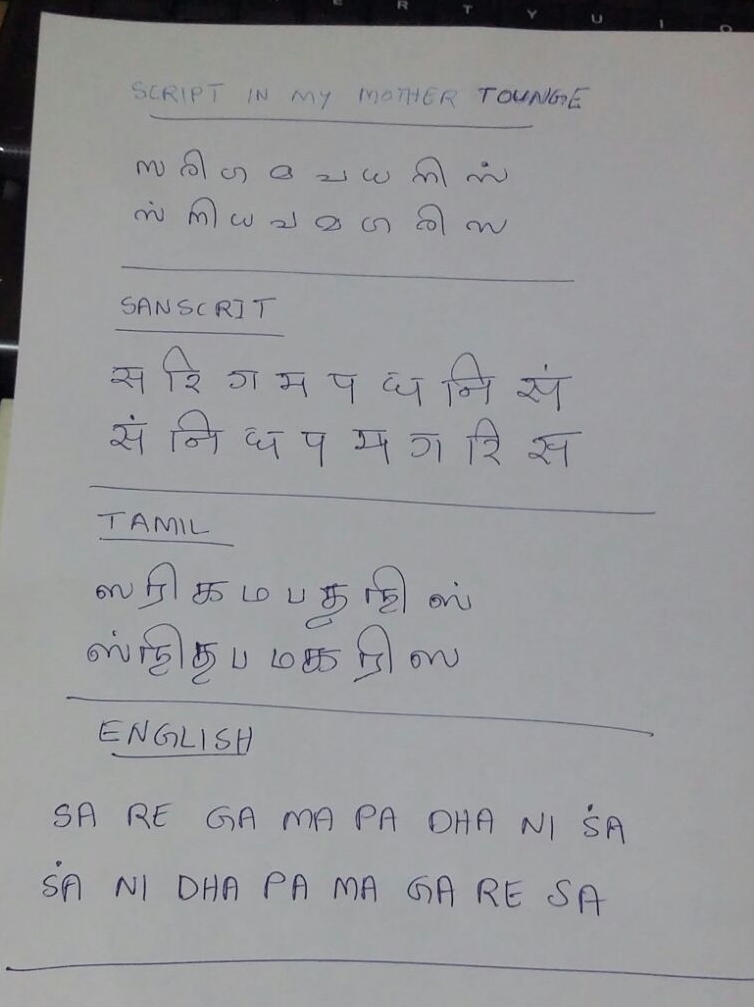

An example of the notation used in classical Indian music. Lazar's mother tongue is Malayalam, but he picked up Tamil quite quickly after coming to Singapore.

If you want to learn classical music in Kerala, you must learn Sanskrit. Our scores are written in that language as well.

It’s very important to be able to teach and communicate music. Only then can you call it classical music. The most complicated rhythm that exists in music is found in Africa, but the problem is that although the musicians know how to play it, they don’t how to teach it. They don’t know how to convey it because it is not systematic and it cannot be taught. If everything isn’t coordinated with strong theory then it can’t really be called classical, and it can’t be kept because it cannot be taught, and therefore it cannot be passed down and spread outside of small family heritages.

If you understand the theory, then learning the instrument is much easier. For example, I was at a party in France one time, and one guest brought a banjo. It was the first time I had ever seen a banjo, but well it’s a string instrument. I borrowed it, tuned it to the way I am used to and started playing. Really, if you me one string stretched taut across this room, I will be able to play for you. Same thing for rhythm, give me a surface, or a dhol (an Indian-style drum) and I will be able to play of hours.

I realize we’ve been talking about Indian music as this homogenous block, but India is so large, so varied and I’m sure the musical traditions vary to some degree between regions. Could you tell us about that?

The music we’ve been talking about so far is South Indian Carnatic music. I believe that many ages ago the music across the area that is now India would have been quite similar. However, after the Mughals and the Arabs invaded, conquered and influenced the Northern part of India, Northern Indian music fused and adopted some of the elements from Mughal and Arabic music traditions.

For example, if you compare some of the more common instruments commonly associated with Indian music. The veena is older, it is a South Indian instrument, whereas the tabla and sitar were invented by the Sufi musician Amir Khusrow. You can see the veena on the older statues in the Southern part of India.

At the same time, I think the music really started to diverge and become clearly distinct when the Natya Shastra came out. The Natya Shastra is considered one of the first books on classical Indian art, and includes chapters on the rules, philosophies and concepts behind music. The tradition it describes is what we call Carnatic music today.

Wow, these differences really go way back in history. Bringing this to the present, how do you go about the fusion of your carnatic classical indian music and jazz? How did this all start?

I was doing my music as per normal as we do in the traditional music tradition following the Indian classical style like everyone else. One day one of my friends introduced Tze to me and asked whether I could do fusion (Jazz and Indian) together. I agreed with not much interest, because I doubted how much a person who did not know Indian music and myself, someone with no idea about Jazz music could collaborate. Then we have fixed a day to jam at Tze's place, and after a few minutes of jamming we both realized that it is interesting to play with Indian Raagas and Jazz chords. They harmonized so nicely and it was a different feeling for both of us. The rhythm and the kind of syncopation is quite similar between jazz and carnatic music.

I understand that you approach music with a kind of reverence and with a strong sense of spirituality. I wanted to know what you meant by spirituality in music and whether this sense of spirituality is diluted when you play fusion music, as compared to purely traditional carnatic music?

Actually the spiritually refers to the attitude with which you approach the learning of music

You have to be dedicated and devoted to what you are playing.

Some people are very strong atheists, but I feel that if you really want to learn music, you must believe in God, or at least you should have some believe in a power, great and intangible, especially with traditional music. I have seen some of my friends, they used to step on instruments [accidently whilst ignoring it], which is considered a big sin. If you step on the instruments, you are not showing the right attitude.

Yes, the instrument was perhaps once clay, but now it is an instrument so it must be treated as such. In the classical tradition it is also very important to show some respect and reverence to the guru, through doing good service for our guru. Back in India, we used to do it with 100% pleasure for our guru even though we had no legal obligation to do so. I just feel like if you don’t have a spiritual attitude and reverence in your mind, you cannot 100% come to the level of respecting the music and the instruments that make the music.

“You should have a strong background in any kind of music, then you can do fusion, if not you will start with fusion and end up with confusion”

I see that’s interesting, the spirituality is in the attitude of the musician, not so much the style of music. Generally, I think there are purists who resist any form of change to the art form, trying to preserve it in its most ‘original’ form. What is your take on this tension between new, more avant-garde forms of art and the more traditional kind?

I think they believe it is a form of service, preserving the music. It is important but if you are too traditional, you cannot convey your music to other kinds of people and your reach is limited. For example, we had this traditional singer in Chennai who would not cross a sea as it is considered a sin by those very strict in their tradition. Anyone who wanted to listen to his music had to go his place to listen to it.

I think when you do fusion, you are also doing a type of service because you are sharing your music with different groups of people, who would otherwise not know about your music. While I say this, I also don’t encourage youths to start with fusion, as I see many do nowadays. You should have a strong background in any kind of music, then you can do fusion, if not you will start with fusion and end up with confusion

You must have a strong background and experience, and you must first get that maturity that comes with years and years of experience, then and only then it will complete the mission as you can share your music with others through fusion.

Why do you think it’s important for the younger generation to retain traditional music?

The problem is, if the younger generation is not interested in the music, later there will be not this kind of music. Our forefathers used to play this, and we understood the value of this music. It is the duty of teachers like me to pass on this knowledge, to keep the culture going on, if not somewhere, when people keep starting with fusion, like evolution, this thing will remain only in CDs and discs and in the past. You have to learn traditional music and you have to pass it on.

An interesting question that comes up here is, in your experience as a teacher, how willing are students to put in effort to learn?

Some students come in thinking that they can attend classes once a week for 1 or 2 years and then they won’t need to come for regular classes. I studied music full-time for 7 years! I think music is like any kind of education or learning – it never really ends. However, if you are able to listen and write the notes down, if you can hear well then I think it’s the point where you stop going for very regular lessons, but of course you must continue learning music. Some people are talented, they have it in their blood, but everyone needs to learn how to write the notes. After all, music is like a language – with a language you should be able to speak, read and write, and with music you should be able to hear, write and play. In fact, I believe that the most important wealth is our ear, it is the head of the department.

For me, the age doesn’t really matter. I can teach a baby who can lie there for an hour, but I feel parents shouldn’t enroll their children ‘for fun’. I’m not saying children shouldn’t have fun, but them learning music should be based on interest in the music.

The language of music is special because it is universal. One time, I was on a train from Bordeaux to Paris and started playing music. Within 10-15 minutes the different people in train all became friends, we had bonded through the music. Communication is made easier with these 7 notes

You have really shared so many wonderful ideas and experiences with us, but I get the sense that we could really keep going for hours. I think we’ll definitely have to come back and interview you again! As the last question for today - if you had to sum up your philosophy for life and for art in 3 words, what would they be?

Art for heart

This interview was held at Lazar’s house, where he also teaches several students. Below are some pictures of the different instruments he has stored at his house(he plays all of them!).

This is a short clip of an impromptu piece Lazar performed for us during the visit. His neighbors love the music, and there are no complaints even when he plays music late at night.